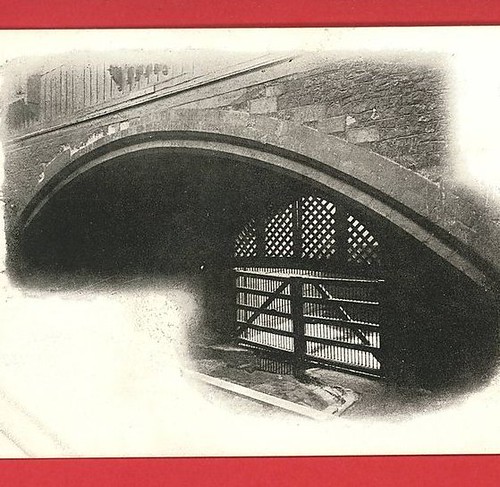

The above view, taken from an early twentieth century postcard, shows Traitors' Gate at the Tower of London, through which visitors to the London tourist attraction are told, prisoners were escorted from the waterside of the River Thames and up the steps on their way to imprisonment in the Tower and possible execution.

Among the prisoners that the doughty black and scarlet-clad Tudor uniformed "Beefeaters" or Yeoman Guards at the Tower inform tourists were led through the gate were Henry VII's second wife Anne Boleyn, who would be executed at the block within the grounds of the ancient Royal castle, and, at a later date, her daughter, the future great Elizabeth I of England, the "Virgin Queen." Stirring history indeed!

Unfortunately, though, it isn't true that those pathetic prisoners, traitors, ex- or future queens and courtiers who has lost favor with the monarch, came that way, according to Dr. Geoffrey Parnell, former historian at the fortress. Dr. Parnell also says in an article in the latest issue of Ripperologist that the location of the block where Anne is said to have lost her head is wrong as well. Oh dear.

Not only that but the famous story that countless visitors have been told over the decades that the famous ravens of the Tower of London have been there for centuries is also a manufactured myth maintains Dr. Parnell in his article, "Riddle of the Tower Ravens Almost Resolved," in Ripperologist 124. Any evidence that ravens have lived at the Tower for centuries is either meager or non-existent. Indeed, the likelihood seems to be that the ravens were given to the Tower by a Lord Dunraven in the nineteenth century. Yes, you read that right, Lord Dunraven. Nonetheless, as Dr. Parnell says, "Visitors to the fortress are told that as long as there has been a Tower there has been a contingent of ravens within the walls" -- the supposed hoary legend being that if the ravens ever left the Tower it would fall.

Dr. Parnell, says, "It is clear that even today much of the popular history on offer at the Tower owes more to the nineteenth-century story telling than historical research." But it makes for exciting and exhilerating history to tell it that way, doesn't it?

As for the story about the Traitors' Gate aka "Watergate", that seems also to be a nineteenth century invention as well.

Dr. Parnell writes: "visitors are shown the stairs leading down to Traitors' Gate and told that the future Elizabeth I of England stopped and protested her innocence on the steps as she entered the fortress as a prisoner during Mary’s reign. In fact the stairs were introduced in 1806 when the waterfilled basin was remodelled and partially infilled. In any event it is known from contemporary accounts that Princess Elizabeth landed at the Privy Stairs towards the west end of the Wharf and that she entered the Tower via the bridge at the Byward Barbican."

Dr. Parnell tells us, "I have studied Tower documents of all sorts for over thirty-five years and I have never come across any official reference to the transportation of state prisoners through the 'Watergate' and up the stairs leading out of the back of the water-filled basin beyond. In fact, the extant basin and stairs were only laid out in 1806 while references to the earlier arrangement (now buried beneath Water Lane) dating from the reign of Queen Mary in the sixteenth century refer to women inhabitants of the castle damaging the stairs by battering their washing on the steps while others laid excrement."

Whoopsie.

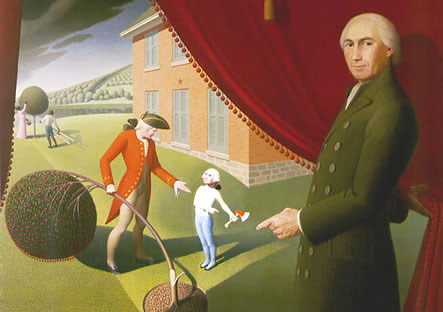

Seeing as it is Presidents Day. I cannot finish without addressing the old story of George Washington and the cherry tree. Of course, the story is part and parcel of the whole mythos about the first American president, and it goes as follows: as a boy, George cut down one of a cherry tree on his father's land. When confronted by his dad, he said, "I cannot tell a lie, father, you know I cannot tell a lie!"

The above view, taken from an early twentieth century postcard, shows Traitors' Gate at the Tower of London, through which visitors to the London tourist attraction are told, prisoners were escorted from the waterside of the River Thames and up the steps on their way to imprisonment in the Tower and possible execution.

Among the prisoners that the doughty black and scarlet-clad Tudor uniformed "Beefeaters" or Yeoman Guards at the Tower inform tourists were led through the gate were Henry VII's second wife Anne Boleyn, who would be executed at the block within the grounds of the ancient Royal castle, and, at a later date, her daughter, the future great Elizabeth I of England, the "Virgin Queen." Stirring history indeed!

Unfortunately, though, it isn't true that those pathetic prisoners, traitors, ex- or future queens and courtiers who has lost favor with the monarch, came that way, according to Dr. Geoffrey Parnell, former historian at the fortress. Dr. Parnell also says in an article in the latest issue of Ripperologist that the location of the block where Anne is said to have lost her head is wrong as well. Oh dear.

Not only that but the famous story that countless visitors have been told over the decades that the famous ravens of the Tower of London have been there for centuries is also a manufactured myth maintains Dr. Parnell in his article, "Riddle of the Tower Ravens Almost Resolved," in Ripperologist 124. Any evidence that ravens have lived at the Tower for centuries is either meager or non-existent. Indeed, the likelihood seems to be that the ravens were given to the Tower by a Lord Dunraven in the nineteenth century. Yes, you read that right, Lord Dunraven. Nonetheless, as Dr. Parnell says, "Visitors to the fortress are told that as long as there has been a Tower there has been a contingent of ravens within the walls" -- the supposed hoary legend being that if the ravens ever left the Tower it would fall.

Dr. Parnell, says, "It is clear that even today much of the popular history on offer at the Tower owes more to the nineteenth-century story telling than historical research." But it makes for exciting and exhilerating history to tell it that way, doesn't it?

As for the story about the Traitors' Gate aka "Watergate", that seems also to be a nineteenth century invention as well.

Dr. Parnell writes: "visitors are shown the stairs leading down to Traitors' Gate and told that the future Elizabeth I of England stopped and protested her innocence on the steps as she entered the fortress as a prisoner during Mary’s reign. In fact the stairs were introduced in 1806 when the waterfilled basin was remodelled and partially infilled. In any event it is known from contemporary accounts that Princess Elizabeth landed at the Privy Stairs towards the west end of the Wharf and that she entered the Tower via the bridge at the Byward Barbican."

Dr. Parnell tells us, "I have studied Tower documents of all sorts for over thirty-five years and I have never come across any official reference to the transportation of state prisoners through the 'Watergate' and up the stairs leading out of the back of the water-filled basin beyond. In fact, the extant basin and stairs were only laid out in 1806 while references to the earlier arrangement (now buried beneath Water Lane) dating from the reign of Queen Mary in the sixteenth century refer to women inhabitants of the castle damaging the stairs by battering their washing on the steps while others laid excrement."

Whoopsie.

Seeing as it is Presidents Day. I cannot finish without addressing the old story of George Washington and the cherry tree. Of course, the story is part and parcel of the whole mythos about the first American president, and it goes as follows: as a boy, George cut down one of a cherry tree on his father's land. When confronted by his dad, he said, "I cannot tell a lie, father, you know I cannot tell a lie!"

The tale, as it was intended to when it was invented, makes Washington sound like a very virtuous person. But the story seems to have been totally made up from whole cloth by a Parson Weems in the early nineteenth century. As you can see, the nineteenth century, with its cloying romantic notions, has much to answer for!

Here's the lowdown on Weems and the tale about wee George and the cherry tree from "The Moral Washington: Construction of a Legend (1800-1920s)" by Adriana Rissetto:

"The story of Washington and the Cherry Tree, a tale which still lingers through probably every grammar school in the U.S., was invented by a parson named Mason Locke Weems in a biography of Washington published directly after his death. Saturated with tales of Washington's selflessness and honesty, A History of the Life and Death, Virtues and Exploits, of General George Washington(1800) and The Life of George Washington, with Curious Anecdotes Laudable to Himself and Exemplary to his Countrymen (1806) supplied the American people with flattering (and often rhyming) renditions of the events that shaped their hero. Weems imagined everything from Washington's childhood transgression and repentence to his apotheosis when 'at the sight of him, even those blessed spirits seem[ed] to feel new raptures' (Weems, 60). According to historian Karal Ann Marling, Weems was struggling to 'flesh out a believable and interesting figure. . . to humanize Washington' who had been painted as 'cold and colorless' in an earlier, poorly-selling biography. While it is likely that some readers of the time questioned the authenticity of the tales, Weems' portraits soared in popularity in the early 1800s."

*********************

On my blog over at Eratosphere, I blogged last week on "All About Mitt... and What the One Hand Doesn't Know the Other Hand Is Doing." Check it out. Also don't forget my new War of 1812 blog.

The tale, as it was intended to when it was invented, makes Washington sound like a very virtuous person. But the story seems to have been totally made up from whole cloth by a Parson Weems in the early nineteenth century. As you can see, the nineteenth century, with its cloying romantic notions, has much to answer for!

Here's the lowdown on Weems and the tale about wee George and the cherry tree from "The Moral Washington: Construction of a Legend (1800-1920s)" by Adriana Rissetto:

"The story of Washington and the Cherry Tree, a tale which still lingers through probably every grammar school in the U.S., was invented by a parson named Mason Locke Weems in a biography of Washington published directly after his death. Saturated with tales of Washington's selflessness and honesty, A History of the Life and Death, Virtues and Exploits, of General George Washington(1800) and The Life of George Washington, with Curious Anecdotes Laudable to Himself and Exemplary to his Countrymen (1806) supplied the American people with flattering (and often rhyming) renditions of the events that shaped their hero. Weems imagined everything from Washington's childhood transgression and repentence to his apotheosis when 'at the sight of him, even those blessed spirits seem[ed] to feel new raptures' (Weems, 60). According to historian Karal Ann Marling, Weems was struggling to 'flesh out a believable and interesting figure. . . to humanize Washington' who had been painted as 'cold and colorless' in an earlier, poorly-selling biography. While it is likely that some readers of the time questioned the authenticity of the tales, Weems' portraits soared in popularity in the early 1800s."

*********************

On my blog over at Eratosphere, I blogged last week on "All About Mitt... and What the One Hand Doesn't Know the Other Hand Is Doing." Check it out. Also don't forget my new War of 1812 blog.

Monday, February 20, 2012

. . . and nothing but the truth

Posted by

Christopher T. George

at

7:35 AM

![]()

Labels: Anne Boleyn, Beefeaters, Elizabeth I, executions, George Washington, History, legends, myths, Tower of London

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment